When Radclyffe Hall decided to write her novel The Well of Loneliness, she knew its lesbian subject would be potentially controversial – not only did she first clear it with her partner, Una Troubridge, she also warned her publisher that the book she was planning would require him to have a lot of faith in her, and stated preemptively that she would not allow any modifications to her text.

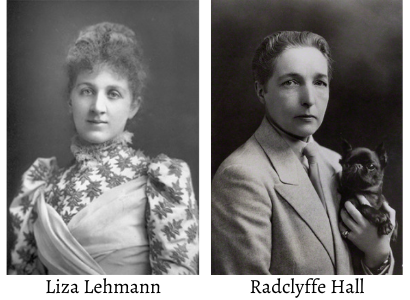

Hall herself was an out lesbian, having lived with Una Troubridge for years, and, before that, Mabel Batten. She was also a successful novelist and poet – her 1926 novel Adam’s Breed had won both the Prix Femina and the James Tait Black prize, a rare achievement. It was this success that made her think that her reputation might make it possible for a novel about “sexual inversion” (the term used by Hall, derived from the writings of Krafft-Ebing and Havelock Ellis, the latter of whom wrote a foreword to The Well of Loneliness) to gain acceptance amongst the general public – and in so doing, to raise public LGBTQ awareness and advocate for understanding in society.

As it turned out, that was an objective that she achieved, albeit at personal cost.

She had already experienced the homophobic media circus of the tabloids in 1920, when she sued St George Lane Fox-Pitt for slandering her as “immoral”. She won her case, but the tabloids had a field day, and the general atmosphere of the times can be seen in its fallout: a Conservative MP proposed a law against “Acts of Gross Indecency by Females”, which cleared the House of Commons but not the House of Lords. (It should be said, though, that this was not because of any enlightened attitudes on the latter’s part – on the contrary, the objection to it, as stated by the then-Lord Chancellor, Lord Birkenhead, was that such a law would bring lesbianism to the attention of women who might otherwise never know of it.)

That said, the initial reception of The Well of Loneliness was largely positive – even the critical reviews had to do with its style rather than its theme, and it was selling so well that the publisher was planning a third print run. Trouble only came when James Douglas, the editor of the Sunday Express, published his editorial – a virulently homophobic diatribe – demanding that the novel be suppressed for its lesbian content. The publisher panicked and sent a copy of The Well of Loneliness to the Home Secretary for review, but unfortunately the Home Secretary wrote back suggesting that the book be withdrawn from circulation. Before long, things escalated into a very public obscenity trial – headed, unfortunately, by a homophobic judge who declared the book obscene, not because of any acts described in the book (it was not explicit in the least), but because its lesbian characters were presented as attractive and admirable. For that reason, therefore, he ordered the destruction of the book, and it was not until 1949, after Hall’s death, that another edition was brought out in the UK.

(In the US, the book met legal challenges as well, when the Society for the Suppression of Vice put in a complaint of obscenity. There, however, she and her publisher won their case – the court declared the novel to not be in contravention of obscenity laws.)

In the long term, despite all these attempts at suppression, Hall did achieve her aims. Not only did the legal struggles of The Well of Loneliness draw attention to the book itself, they also (especially in the case of the UK trial) increased the general public’s awareness of institutionalized homophobia, even in Hall’s time. The thousands of letters of support she received after the trial attest to that – she heard both from gay people who drew comfort from the novel and the presence of a protagonist with whom they could identify, as well as straight people who wrote to express sympathy at the way the trial had treated her, or to speak of how the book had changed their attitudes, suggesting that she was indeed an agent of the change that she sought to effect with her brave stand for equality.

-Suzanne Yeo

September 2020

Return to podcast. ↵

Can’t get enough?

Visit our Bibliography page for further sources.

Subscribe to our Newsletter!